- Home

- Andrew Lanh

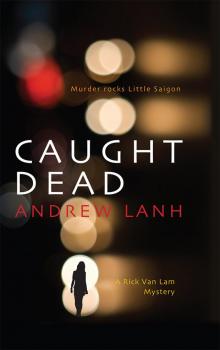

Caught Dead

Caught Dead Read online

Caught Dead

A Rick Van Lam Mystery

Andrew Lanh

Poisoned Pen Press

Copyright

Copyright © 2014 by

First E-book Edition 2014

ISBN: 9781464203336 ebook

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in, or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form, or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise) without the prior written permission of both the copyright owner and the publisher of this book.

The historical characters and events portrayed in this book are inventions of the author or used fictitiously.

Poisoned Pen Press

6962 E. First Ave., Ste. 103

Scottsdale, AZ 85251

www.poisonedpenpress.com

[email protected]

Contents

Caught Dead

Copyright

Contents

Dedication

Prologue

Chapter One

Chapter Two

Chapter Three

Chapter Four

Chapter Five

Chapter Six

Chapter Seven

Chapter Eight

Chapter Nine

Chapter Ten

Chapter Eleven

Chapter Twelve

Chapter Thirteen

Chapter Fourteen

Chapter Fifteen

Chapter Sixteen

Chapter Seventeen

Chapter Eighteen

Chapter Nineteen

Chapter Twenty

Chapter Twenty-one

Chapter Twenty-two

Chapter Twenty-three

Chapter Twenty-four

Chapter Twenty-five

Chapter Twenty-six

Chapter Twenty-seven

Chapter Twenty-eight

Chapter Twenty-nine

Chapter Thirty

Chapter Thirty-one

Chapter Thirty-two

Chapter Thirty-three

Epilogue

More from this Author

Contact Us

Dedication

for Xuong and Xia

Prologue

It’s always the same dream. Except it’s not a dream; it happened. This moment again and again drifts back to me during restless, sleepless nights. I lie in bed, pushing covers onto the floor, and I remember. But I can’t really remember, even though I was there. My mother told me the story when I was a five-year-old boy, running around the dusty streets. It was her favorite story, and I plagued her with questions. So now it is, in fact, my own story.

You see, I’m probably a year old, living with my mother in Saigon. She’s nervous, a little frightened—she holds me too tightly, as though she knows she will not always have me in her lap, in her life.

I’ve just learned to crawl. The long war is over but the killing and screaming and pain never seem to end.

Her mother—or some older woman in the bombed-out neighborhood—tells her that the little boy will have a tough life now that the Americans have fled. My mother nods, her eyes dark with fear. She looks at the half-Vietnamese, half-white son she holds. She tightens her grip.

Everyone has a bowl of rice in the afternoon. The scarce drinking water is so murky some people spit it out, curse. The sweet aroma of jasmine battles the stench of burnt wood. The stone house where the baby is cradled is missing part of a wall.

“We’ll see his future.” The old woman takes the whimpering baby boy from his mother’s arms. What follows is familiar Vietnamese custom. Let the crawling baby reveal his destiny. People drift over, gathering outside the tiny house with the missing wall, the roof partially caved in. In the dusty, hard-packed courtyard, swept free of papers and chicken bones and dog droppings, the old woman draws a lopsided circle with a stick, positioning the boy in the center. He cries, looks for his mother, falls back onto his side, and then struggles to right himself. Five feet away, the women place small objects, speckled around the edge of the sloppy circle. My mother remembers a pencil, a stale moon cake, a bowl of rice, other bits and pieces. But over the years my dreams have added other items—crumpled paper money, a vial of some elixir, a torn newspaper. I add others with the years.

The mood is festive, buoyant. The neighbors watch. A woman slices an overripe mango; the juices run over her hands. Nearby some men abandon their game of tam cuc, leaving the cards still spread on the table. They joke, cigarettes bobbing in the corners of their mouths. My mother waits, but the baby doesn’t move. In a small voice she calls out to little Viet Van Lam, “Come, my boy, come.” The baby stares at her, a smile on his skinny face. Finally, joyful, he crawls.

They wait. The laughter stops. Now the baby will choose his life. They wait, believing. If the baby crawls to a pencil, he will become a writer, perhaps. If he crawls to a cake, a baker. Money—a banker. Rice—a farmer.

But there are traps, my mother whispers to me later. There are evil omens, symbols of darkness, of loneliness, of disease. Pieces of crumpled black crepe paper. A jagged rock from the nearby fields to suggest a life laid low by nagging want. The tattered shirt of a life of abject poverty, a seeker after alms. The incense stick of early mourning.

They watch. The baby crawls.

Grimy and gurgling, he approaches the bowl of rice. They nod approvingly. He will be a farmer in the fields outside Saigon, now Ho Chi Minh City. Yes, a hard life, but respectable. A life of getting by.

But the toddler shifts direction. Suddenly, in a rush, he lunges toward a tiny wooden dragon painted deep black with a fiery-red shellacked tongue, shiny eyes, razor-sharp tail, and triumphant outstretched wings. With his thin little fingers the boy brushes the miniature emblem.

But then, turning slightly, he grabs a grotesque figurine, a black-stained gargoyle, a fearsome demon. An old farmer had tossed it onto the edge of the circle, this roughhewn clay figure, purposely awful, with its big head, bulging eyes, and terrifying grimace. This, they know, is darkness, evil. This, they know, is the path away from light. At that moment the people gasp, unhappy. The old woman closes her eyes. His mother starts to sob. For the baby has chosen a life of wrongdoing and woe, the sinister clay demon that foretells crime: thievery, brutality, lying, corruption, even murder.

No one breathes.

The boy holds the figurine over his head, waves it, while his mother weeps.

But then little Viet Van Lam grabs it with both hands and, displaying a strength not shown before, he smashes it to the ground, breaking off its head, snapping off the twisted arms. The demon lies broken by his bare feet, covered in dust. The boy looks for his mother.

She remembers that he grins as he grasps the wooden dragon, tightens his fingers around it.

Everyone starts to applaud. Laughs and yells. The men nod at the boy, grinning. The old woman leans into the mother he will lose within a few years. “Your son,” she whispers, “will be a policeman.” She touches the head of the little boy, now back in his mother’s lap, his unusual blue eyes wide and alert. “A seeker after justice,” she says. “Buddha’s boy.”

Chapter One

Everyone had heard of the Le sisters. Even outside the closed Vietnamese community in Hartford, “the beautiful Le sisters” were talked about. They’d been stunners in their twenties, but even now, well into their forties, they caught your eye. So when Hank phoned me one night, waking me from an early sleep, all I heard was “the Le sisters,” and I supplied the obligatory adjective: beautiful.

“Rick, wak

e up,” Hank yelled. “Mary Le is dead.”

I wasn’t fully awake. “What?”

I could hear annoyance in his voice. “Mary Le Vu. You know, one of the beautiful Le sisters.”

One of the beautiful Le sisters. Twin sisters. I scratched my earlobe, sat up on the sofa where I’d drifted off to sleep around nine.

“What?” I yawned.

“You listening to me?” Hank yelled again into the phone.

I tried to picture the sisters. I’d met them a few times, usually at some Vietnamese New Year’s wingding, some Tet over-the-top frenzy, once at a wedding where all the men got drunk, and another time at a Buddhist funeral.

“I’m sleeping,” I explained.

“It’s not late.”

“I had a long day.” I’d gotten up to jog at six, avoiding the hot, relentless August sun of a heat wave that was in its third day.

“She’s dead,” he blurted out. “She’s been murdered.” He waited. “Did you hear me?”

I was awake now. “Xin loi,” I mumbled. I’m sorry. I knew the sisters were distant cousins of Hank’s mother, a vague connection reminding me that many of the Vietnamese in metropolitan Hartford were somehow biologically or emotionally connected—intricate family bloodlines or spirit lines that somehow radiated back to the dusty alleys of Saigon and forward to the sagging, fragmented diaspora of Connecticut and Massachusetts. Sometimes, it seemed, everyone was an uncle or aunt to everyone else.

“Which one was she?” I stammered.

He didn’t answer. “Can you come to my house? It’s important.”

“What happened?”

Again he didn’t answer. “Can you meet me here?”

“Now?”

“Yes.”

***

After throwing on shorts and a T-shirt, retrieving my wallet and keys, I drove from my Farmington apartment to the poor East Hartford neighborhood off Burnside where Hank lived with his family in a small Cape Cod in the shadow of Pratt & Whitney Aircraft. I knew better than to refuse Hank’s request. Not only the insistence—and mild panic—of his voice, but the unspoken message that Hank, the dutiful son, was doing this for his mother. In his early twenties, taking the summer off from the Connecticut State Police Academy where he was training to become a state trooper, Hank was a former student of mine in Criminal Justice at Farmington College. He’d become my good buddy.

He opened the door before I knocked, shook my hand as if we’d just met last week, and nodded me in. A lanky, slender young man with narrow dark brown eyes and prominent cheekbones, he wore sagging khaki shorts and a T-shirt. It was a sticky August night, even though the sun had long gone down, and he was sweating.

His mother, Tran Thi Suong, embraced me, and then burst into tears. “Rick Van Lam.” She bowed. “Cam on.” Thank you. Hank looked uncomfortable. His grandmother, quiet as a shadow, drifted in, nodded at me, and then disappeared. She was wearing her nightclothes, a small embroidered white cap on her white curls. As she left the room, she touched her daughter on the shoulder, and whispered, “Y troi.” God’s will.

Hank’s mother said something in garbled, swallowed Vietnamese, burst into tears again, and turned away. Hank, bowing to her, motioned for me to follow him through the house. Passing through the old-fashioned kitchen with the peeling wallpaper, I saw the narrow makeshift shrine high on the wall by the door. The plaster-of-Paris Virgin Mary stood next to a tubby Buddha, both surrounded by brilliant but artificial tropical flowers, a couple of half-melted candles, a few joss incense sticks, and some blood-orange tangerines. Scotch-taped to the wall nearby was a glossy print of Jesus on the cross.

Outside, sitting in my car, Hank apologized. “I’m sorry, man. Let’s drive. I didn’t realize my mother would, well, shatter like that when you walked in.”

I was rattled now. “Hank, what the hell is going on?”

He drew in his breath. “I told you. One the two beautiful Le sisters—murdered.” I winced at that. “Mary was my mother’s favorite, someone she was close to as a small girl in old Saigon, someone she would meet on Sunday morning for mi ga and French coffee.” Chicken soup for the Asian soul.

“And?”

He sighed. “Mary was murdered earlier tonight at Goodwin Square in Hartford, you know, that drug-and-gang neighborhood. It seems she got caught in some gunfire, some drive-by shooting with local drug dealers who…”

“Wait!” I held up my hand. “I’m not following this.”

He looked exasperated. “Mary, who never left her home in East Hartford or her husband’s grocery in Little Saigon, for some reason wandered into that godforsaken square and somehow got herself shot.”

“In her car?”

“I don’t know.”

“Why was she there?” I knew that notorious Hartford square—shoot ’em up alley.

“Hey, that’s the million-dollar question, Rick. She knew better. Everyone in Hartford, especially the Vietnamese, knows better than to go there. That’s no-man’s-land. You get that. It’s not even near Little Saigon.”

We hadn’t left the driveway, the two of us sitting there, now and then staring back at the house. His mother’s shadow slowly moved across the living room. A woman who couldn’t sit down.

“Where are we going?” I turned on the ignition.

“To the scene of the shooting.”

“Why?”

“Well,” he dragged out the word, “when the news came tonight, an hour or so ago, when Uncle Benny called and then it was on the news, Grandma held her hands to her face and said, ‘No!’”

“No?”

“She was quiet a long time and then she said ‘No!’ again. When I asked her what she meant, she told me, ‘This is not as easy as it seems. If this seems to make no sense, then there is nothing but sense involved.’ I said, ‘Grandma, I don’t get you.’”

I smiled at Grandma’s words. In my head I could hear her soft, melodious rendering of ancient wisdom. Hank was raised a Catholic by his father, but his mother’s mother held to the tenets of Buddhism, the two religions coexisting in the often volatile household, with Hank caught in the middle. The Virgin and the Buddha.

So now I said to him, “Well, Hank, she’s telling you she thinks something else is going on here.”

“I don’t see it.”

“What I don’t see, Hank, is why I’m here.”

He smiled, a little sheepishly. “Your name came up.”

“Why?”

“Grandma always thinks of you. You know, you and her, the two Buddhists in the house. In fact, she said something about a hole in the universe that only you can fill.”

I groaned. “Wait, Hank. She expects me to find the drug dealer with a semiautomatic and a posse behind him? In Hartford? Where the local economy is sustained by drug trafficking and life insurance?”

“You are an investigator.”

“I do insurance fraud.”

“But you know Grandma. She thinks you can see through plywood.”

“And she asked that I get involved?”

He smiled again. “As I say, your name came up.”

***

At Goodwin Square, off Buckingham and Locust, the usual late-night drug dealers on duty had decided to go for coffee or to oil their revolvers in the privacy of their own cribs. A beat cop stood by his lonesome on the southwest corner of the square, outside the obligatory yellow tape. A crew of evidence technicians, scurrying back and forth to a van, was still working the scene, photographing, charting, measuring. But the body had been removed, I noticed. There was some slow-moving, rubbernecking traffic, a few local idlers huddled nearby, but the square was eerily quiet. Storefronts looked beat up and tired. Just a narrow block of broken sidewalks, flickering streetlights, hazy neon signs with burned-out letters, and two stripped, abandoned cars by an alley. And fresh blood stains. Satan’s Li

ttle Acre, the locals called it.

Hank glanced at the old-model Toyota with all its doors open. Mary’s car, I figured.

“Just talk to the detective.” He stepped closer to the yellow tape.

“All I see is a cop.” I pointed. “And he’s looking at us like we’re the Yellow Peril.”

I approached him, leaning in to catch his name: Lopez.

An unfriendly look. “Help you?”

I told him that the murdered woman was a relative of Hank, and I was a private investigator from Farmington.

“From Farmington?” His clipped voice said the name of the moneyed suburban town with a hint of contempt. “What do you investigate there? Lost stock portfolios?” He looked pleased with himself.

“Who’s the detective on this case?”

He pointed over his shoulder, past the yellow tape, past the busy evidence team, through the plate-glass window of a storefront that announced: “Cell Phones! Phone Cards to South America!” I saw a short, wiry man, late fifties, mostly bald with a fringe of hair over his collar. He reminded me of an aging fighter, a tough bantam rooster. He looked bored. He scratched his belly absently, and then, for some reason, licked his index finger. When he walked out, the cop called him over and nodded toward us.

“Family,” the cop said, “and a country-club PI.”

The detective didn’t look happy to see us. “Yeah?” He stepped around the yellow tape, yelled something to one of the members of the evidence crew, and then purposely stood ten feet back, watching us.

“My name is Rick Van Lam.” I was bothered by the space between us. “And this is Hank Nguyen, a relative of Mary Vu’s. I’m a PI with Gaddy Associates, and the family asked…”

“It’s a drive-by.” He cut me off. “Some loser drug dealer speeds by, maybe sees competition strolling on his turf, opens fire, bang bang, and the innocent lady who just got out of her car and didn’t know where the fuck she was—well, she gets it in the head. The lowlife scum drives off to annoy another one of my days.” He reached for a cigarette from a crumpled pack, lit it, and exhaled smoke. His face relaxed for a second. “Satisfied?” He turned away.

Child of My Winter

Child of My Winter No Good to Cry

No Good to Cry Caught Dead

Caught Dead Return to Dust

Return to Dust