- Home

- Andrew Lanh

No Good to Cry

No Good to Cry Read online

No Good to Cry

A Rick Van Lam Mystery

Andrew Lanh

Poisoned Pen Press

Copyright

Copyright © 2016 by Andrew Lanh

First E-book Edition 2016

ISBN: 9781464206429 ebook

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in, or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form, or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise) without the prior written permission of both the copyright owner and the publisher of this book.

The historical characters and events portrayed in this book are inventions of the author or used fictitiously.

Poisoned Pen Press

6962 E. First Ave., Ste. 103

Scottsdale, AZ 85251

www.poisonedpenpress.com

[email protected]

Contents

No Good to Cry

Copyright

Contents

Dedication

Prologue

Chapter One

Chapter Two

Chapter Three

Chapter Four

Chapter Five

Chapter Six

Chapter Seven

Chapter Eight

Chapter Nine

Chapter Ten

Chapter Eleven

Chapter Twelve

Chapter Thirteen

Chapter Fourteen

Chapter Fifteen

Chapter Sixteen

Chapter Seventeen

Chapter Eighteen

Chapter Nineteen

Chapter Twenty

Chapter Twenty-one

Chapter Twenty-two

Chapter Twenty-three

Chapter Twenty-four

Chapter Twenty-five

Chapter Twenty-six

Chapter Twenty-seven

Chapter Twenty-eight

Chapter Twenty-nine

Epilogue

More from this Author

Contact Us

Dedication

To the memory of Lam The Do

1974-2009

Prologue

My cot is in the far corner of the barracks-like room. Twelve cots clustered together, no breathing room, and mine is by the crumbling wall where water seeps through the cracks. Chattering mice crawl in and out, scavenging for maggots or hard grains of rice. At night, restless, my stomach churns from the stench of stagnant sewage, rotting bamboo, and mice droppings. The worst cot in the room, given to me by the good nuns because I’m the worst of the boys—impure, a skinny twelve- or thirteen-year-old with forbidden American blue eyes and a rigid jaw. Sister Do Thi Bich, the old nun who runs the Most Blessed Mother Orphanage, refuses to say my name. Instead she sneers, “Ma quy nuoc ngoai.” Foreign devil. Satan’s boy, beaten by the other orphans for sport.

But that changes.

One afternoon, returning from the market on Nguyen Tat Thanh with a heavy load of lemongrass—the reeds are wrapped in a cheap rag-paper flyer carrying Uncle Ho’s benign face—I hear sobbing from the hallway outside La Vang Chapel. Then, a burst of high laughter, crazy, almost maniacal. I drop the lemongrass on the cook’s counter and rush back toward the barracks.

The boy I come to know as Le Xinh Phong is surrounded by a gaggle of jeering boys, circling him, poking him, tugging at the cheap shirt he wears. Whore’s son, they yell. Nguyen rua. Cursed boy. Leper.

My heart swells with a curious and welcome joy: another dust boy. Bui doi. Yes, the lazy, slanted eyes but the rich mahogany complexion of old coffee. A black boy.

Sister Mary Le Phan, who guards us, stands with her arms folded over her chest and watches as the others harass the boy, yet does nothing. A hint of a smile on her wrinkled face, which does not surprise me. She keeps a bamboo switch in her room. When she turns and catches me watching her, she fumes, wags a shaky finger at me, and croaks out my name. “Lam Van Viet.” The boys stop poking the newcomer. One jeers, “The other one.” A little boy looks up at the good sister and says, “Nguoi pham toi.” The sinner.

Barking orders, Sister Mary relocates my cot, forcing Phong to rest in my old spot—the sinner’s corner. Quiet, shaking, he lies on his back that first night and stares at the ceiling. In the middle of the night, everyone sleeping, he sobs quietly.

The devil has come to the orphanage. Qui Satan.

Phong is bigger than the rest of us, a chubby boy with a wide face, a bulbous nose, so I am not surprised he becomes everyone’s favorite leper. Especially mine, I’m ashamed to admit. For a few scant seconds of bleak eternity, I can catch my breath. Yes, I am punched and shoved, mocked—the whore’s son, the American pig’s boy, the familiar litany—but my cursed white blood oddly gives me a momentary pass. Not so Phong, whose G.I. daddy has left him that sable skin.

One afternoon I hear two nuns chatting about him. Sitting in the small garden, the scent of jasmine and burnt charcoal covering the yard, they talk of their Christian duty, one more cross to bear, yes, yes, yes. Sadly, yes. Wounds in the body of Jesus Christ. Some pesky government officials found the boy wandering in a village outside Ho Chi Minh City, stealing rice to survive, sleeping under a banyan tree, a boy covered with green bottle flies. When they located his family nearby, they learned his shunned mother had died—murdered, in fact—so an uncle pushed him out.

Phong is frightened of everyone.

Then I begin my own sinning. When the other boys taunt him, beat him so that there are always purple welts on his face and arms, I join in. I have someone to hate—to hit. My blows are furious and cruel, the worst of them. My fury is savage—so much so that the other boys somehow look at me with a grudging respect, if a little wariness. Never to be included in their games or talks or adventurous begging at the Soviet hotels on Nguyen Hue Street, nevertheless, I am the enforcer, my tight fist crashing into Phong’s vulnerable ribcage.

He takes it. He even tries to be my friend because he has no one else. Lonely, yes, stuck in that corner, he tries to talk to me. I shun him. I call his mother a whore, his father a black bastard. I curse him. “Ban se dot chay trong dja nguc.” You will burn in hell.” The other boys applaud me.

One day there is a lot of scurrying in the hallways, the nuns frantic. We boys are lined up, headed back to the barracks after Sunday morning services, but the nuns hurry us, shush us.

“Quiet, quiet. Jesus is listening.”

We are told our lunch is delayed, to stay in the room, to pray, but I sneak out to spy on Mother Superior, Sister Do Thi Bich. In her cramped office she is whispering to two men who’ve arrived in a noisy car. One man is obviously government, a small, officious man in pristine military uniform, his chest covered with garish braid and gleaming buttons. He speaks in a loud booming voice, like rocks smashing a wall, and Mother Superior keeps bowing and humming at him, squeaking out nonsense words. Next to him sits an American—or at least I assume him to be an American. A tall black guy with a scraggly beard. Bushy sideburns, a cigarette bobbing in his mouth. He wears a peasant’s tunic, ill-fitting because the pants ride up a shin exposing old ripped socks.

When they stand up, I scurry back to my cot.

Within minutes, Mother Superior enters our barracks and points at Phong, who huddles under his thin blanket, frightened. “You,” she thunders, and the black man shoots her a look. Phong stumbles toward them.

Late that afternoon I spot the man walking with Phong, too much space between them, but the uniformed man is nowhere around. When Phong returns to our room, he looks confused, but there is also fear in

his eyes. Strangely, I catch him smiling at one point, but that stops quickly when he notices my eyes on him.

The boys buzz and titter about the visit. Someone says the black man is an American deserter who worked with the Viet Cong—an American traitor. He went into hiding when the Americans abandoned the country in 1975. Now working for Uncle Ho’s Communist government, he is looking for his child, born in the last days of the war.

We call him the black American. Le Den.

The next day, at twilight, pruning the dead leaves from the mango tree near Mother Superior’s office, I hear his voice from behind the closed door. He speaks Vietnamese with a thick lazy drawl, some words difficult to understand, stammered, broken. But what I do understand is that Mother Superior has reluctantly opened a huge ledger on her desk, which the man keeps referring to. His voice is stinging, harsh. Through a crack in the door, I watch as his fingers drum the sheets.

He doesn’t look happy, and the good sister apologizes over and over. He stands up, he sits back down, he rocks in his chair. At one point his fist slams the ledger, and it shifts toward the edge, grabbed in time by the sister.

What I learn slams me: someone at the orphanage has recorded names, tidbits of information, birth certificates, family papers—all about the boys dropped off at the orphanage. But what the man discovers does not please him, and he fumes. Yes, the nun says, we have some information on the American fathers, if provided. An I.D. card maybe. In one case dog tags of a dead soldier.

Wide-eyed, I wonder—me? What about me? A dim memory of my mother when I am around five, a woman who holds me tightly in her lap, who tucks into my breast pocket the slender volume called Sayings of Buddha that I will carry to America—and cherish all my life. Does the ledger have her name? I quake—the name of the American soldier? My father? My family? I stare at the ledger through the tiny opening in the door as though it is a holy talisman, a grail lit by fire and wonder.

The man never returns to the orphanage.

Phong sleeps with his face to the stinky wall.

Within the year I am sponsored to America, shuffled off with little notice, a paper bag with a change of clothing and that slender volume from my mother. Nervously, I huddle in the backseat of a Soviet car next to Sister Mary Le Phan. As the car pulls away from the orphanage, I spot a gang of boys chasing Phong into an alley. He trips over a basket of stale bread, an old woman cursing him, pummeling him. The boys land blows on him, and his helpless cries mix with their horrible laughter. Dazed, he lies there, his right arm bent under him.

Suddenly I am sobbing. Startled, the nun slaps me, though she glances at the man sitting in the passenger seat up front. She apologizes to him, a rasp in her throat.

Pinching me, she whispers, “Shut up, you bastard. No one cries in America.” She snarls her words. “Con de hoang.” Bastard boy. “Do you want to go back to the orphanage?” She draws her face close to mine. The stink of chewed betel nut. “Do you, you ungrateful boy?”

Chapter One

The phone inside my apartment was ringing as I fumbled for my keys. It stopped, then started again. Then my cell phone jangled, a ring tone that blared a few swollen bars of Billy Joel’s “Piano Man” I’d been meaning to change. I reached into my pants pocket, but realized I’d left the phone in a jacket hanging just inside the locked door. It stopped jangling. The land line rang again, and now I could hear an anxious voice, calm but laced with worry. Liz’s voice. My ex-wife.

Disaster, I sensed.

“What?” I yelled into the phone. But Liz had hung up.

I toppled into a chair, caught my breath.

I’d been jogging on Main Street, across from the campus of Miss Porter’s School, enjoying the late-afternoon April air, brisk and invigorating, the first hint of a glorious Connecticut spring. But I’d run too far, savoring my rhythm, a song in my head, the crisp air slapping my face.

I dialed Liz back. “Liz? Tell me.”

She breathed in. “Jimmy.”

One word. My mind went blank.

My partner in insurance fraud investigations, based out of Hartford. I was his partner in Gaddy Associates. Jimmy Gadowicz, the seventy-something blustery man who took me in as his partner years back and became a man I loved and respected. Steel-eyed Vietnam vet with the no-nonsense work ethic, he wouldn’t let me get away with anything but ironically let me get away with everything. I know that sounds contradictory—if a little glib—but the man had a way of making sure your aim was true because, in fact, that’s the way he demanded the world behave.

“Tell me,” I whispered.

“He’s been hurt. Alive—but hurt.”

I slipped back in the chair and gripped the telephone. “Tell me.”

I could hear Liz’s heavy sigh. “It just flashed across the TV, his name, misspelled of course, and I called a friend at Hartford PD…”

I broke in. “Liz.” My voice too loud. “Jimmy.”

“He was walking on the sidewalk near your office. Down Farmington Avenue. With his friend, Ralph Gervase. Two muggers attacked them. One slugged Ralph, who fell, hit his head.” A deep intake of breath. “He died, Rick.”

“Oh, my God.” I closed my eyes.

She waited a heartbeat. “Jimmy was hit by a car.”

“What?”

“I don’t have all the facts. When Ralph was clobbered, Jimmy stepped back into the street and a car hit him.”

“He’s alive.”

“He’s alive,” she echoed. “He’s at Hartford Hospital. I’m headed there now.”

“I’ll meet you there.”

I hung up the phone and realized I’d been gripping the receiver so tightly my knuckles were white.

Standing up, I was momentarily dazed as I glanced around my apartment, staring at familiar objects—that old Tiffany-style lamp I bought at Goodwill and painstakingly rewired, the country-store work desk with my computer and green-glass desk lamp. Oddly, everything now struck me as alien, objects lit by a curious glow.

Shaking myself out of my trance, I rushed into the bedroom and stripped off my running clothes, dropping everything onto the floor, kicking my sneakers across the room. I slipped on old jeans and a flannel shirt, buttoned it so quickly I had to begin again because I’d buttoned it crookedly. I grabbed my spring jacket, checking to see whether my cell phone was in the pocket. Then I lingered by the front door, hesitant, taking in my comfortable rooms. An ivy plant on a sideboard needed to be repotted. Why hadn’t I noticed that before? I was afraid to leave—afraid to drive the fifteen or so highway minutes into Hartford—afraid of what I’d find when I entered Jimmy’s hospital room.

My apartment is on the second floor of a glorious Victorian painted lady, all gingerbread decoration, its clapboard sides painted a brilliant canary yellow, the favorite color of my landlady, Gracie, who lives on the first floor. Threadbare orientals cover the landing, but the boards creaked and moaned with each step I took.

A shaky voice drifted up from the first floor. “Rick.” Tentative, shaky.

Rushing down the steps, I met Gracie, her wrinkled face trembling. “Rick,” she repeated.

“Gracie, what?”

“The radio.” A deep sigh. “Jimmy.”

So she’d heard.

“Jimmy’s all right,” I assured her, though I wondered about my own words.

Gracie took a small step toward me. She was dressed for going out in her black opera cape. An old woman, probably early eighties, tall and slender with abundant white hair forming a bushel barrel of loose ends speckled with hairpins, she’d been an “entertainer”—her favorite word—since she was a young girl. A Radio City Rockette until an enterprising young businessman, hopelessly smitten with the beauty, had squired her off to Connecticut and this gigantic home. Now, standing close to me, her face flushed, she drew the cape tighter around her body and nodded toward the front entrance.<

br />

“No, Gracie, I’ll call you.”

She shook her head vigorously. “You can’t tell an old lady what to do, Rick.”

I smiled. “I’ve learned that.”

“Then why are we standing here?” She pushed by me. “Move, then.”

I shrugged and followed her out the door.

Gracie was smitten with Jimmy, as he with her, though both skittered around each other. It often reminded me of a scene from an old Annette Funicello-Frankie Avalon teen movie I’d watched one night on MeTV. For a boy who hadn’t stepped onto American shores until he was thirteen or so, fresh from a Vietnamese orphanage, such black-and-white late-night reruns were a wonderful education, if skewed. I baited Jimmy and Gracie, we all did, our gang of friends, but we loved them to death.

“I’ll bring the car around,” I told her.

“Rick.” A squeaked-out word.

“What?”

“They said Ralph Gervase is dead.”

“Liz told me.”

Her eyes got moist. “I never liked him, Rick. That Ralph. The few times we met. I disliked him.” She shivered. “I always thought he was unpleasant. I didn’t like him hanging around with Jimmy.”

“I didn’t like him either, Gracie.”

She looked over my shoulder. “I feel bad saying that.”

“It’s all right. You can’t like everyone.”

She clicked her tongue. “For an educated man, you do like to use clichés.”

I smiled back at her. “I learned a long time ago that in America they serve as wonderful transitions when you need to say something.”

Without smiling, she glared at me. “How about this—Silence is golden.”

I left her on the front porch, headed out back to get my car.

Ralph Gervase, dead.

I stopped walking as I recalled that Jimmy had invited me for lunch with him and Ralph that afternoon. He’d asked me to meet them at our new office in a three-story building on Farmington Avenue—we occupied the second floor, Jimmy huffing and puffing his way up one flight of stairs, a glowing Lucky Strike bobbing in the corner of his mouth—and the three of us would go for a bite at some local eatery. Now, thinking about that invitation, I bit my lip. I’d dug in my heels, refused because, like Gracie, I disliked Ralph Gervase.

Child of My Winter

Child of My Winter No Good to Cry

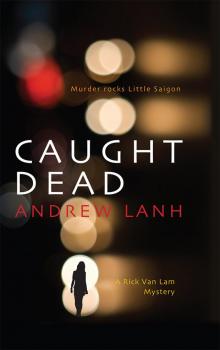

No Good to Cry Caught Dead

Caught Dead Return to Dust

Return to Dust