- Home

- Andrew Lanh

Child of My Winter Page 2

Child of My Winter Read online

Page 2

“Neither one of us believes that.”

***

A week before Thanksgiving the solitary life of young Dustin Trang shifted, a metamorphosis I’d not expected. Yes, Hank had persisted in greeting the young man in passing, even dipping into a seat to annoy him, but Dustin had remained stoic, withdrawn, resisting Hank’s charm crusade.

That changed.

One night, sitting by myself with a hamburger and coffee in the College Union, I watched a teacher sidle up to Dustin and loudly praise a term paper he’d just graded. He was walking past Dustin’s table, followed by a swarm of buzzing acolytes, and suddenly he stopped and announced in a loud, enthusiastic voice, “Dustin, I gotta tell you—your paper on local evangelical churches and the New England Great Awakening—you nailed it.”

Dustin sputtered feeble thanks, then dropped his eyes down at his textbook. But the professor wasn’t through. Stepping near, he tapped him on the shoulder and said, “I mean it, Dustin. You nailed it.” Dustin refused to look up.

Ben Winslow—Dr. Bennett Winslow, Professor of Sociology—was the campus firebrand activist and all-around good-natured prof. “Call me Ben,” he told his students, and they did, though some with derision and mockery. A man in his sixties, a roly-poly Falstaffian man with round cheeks, white beard stubble, skimpy salt-and-pepper hair, an infectious laugh, he had the noisome habit of lecturing so loudly other teachers closed their doors in his corridor. An unreconstructed sixties radical—his own Facebook definition and Twitter handle @socialdemocrat—he was immensely popular, not only because of his dynamic, off-color, pun-sputtered lectures, but because his real concern was his students. A rarity. With his rolled-up work shirt sleeves and Beatles neckties, his corduroy sports jacket with ripped elbows, he was the campus oddity. A claque of worshipful students trailed after him. Twice a week, after his Social Problems course ended at seven, he’d linger in the Union, surrounded by a coterie of students, and the gabfest would go on.

Suddenly, surprisingly, Dustin Trang became a part of his circle. Certainly not one of the boisterous kids who celebrated everything Winslow said as though they were part of the studio audience of, say, Jimmy Fallon on late-night TV. No, Dustin sat on the edge of the group, inordinately happy that someone included him in a party. I doubt whether he ever spoke—the few times I spotted him among Winslow’s followers he sat at attention, ready to bolt if too much notice came his way. The fact that he had found his way there pleased me.

“See,” I nudged Hank one night when we strolled past the chatting students. “Ben Winslow hath charms to soothe the lonely boy.”

“I needed more time,” Hank quipped.

He was pleased, I knew. Passing, Dustin glanced at us, and Hank flicked his finger toward him and smiled. Dustin actually smiled back.

“Professor Winslow wants everyone to love him,” Hank told me.

“So do you.”

He made an exaggerated monkey face at me, which startled a young girl walking toward us. The tall state trooper in dress uniform made a grotesque face. Her eyes got wide.

He leaned in. “I’m gonna have to arrest you, Rick. Otherwise she’ll think the state police are crazy.”

“Perhaps you should assume a more stoic look when you walk through these hallways.”

“I don’t like going out of character.” He raised his eyebrows. “Look.”

Professor Winslow’s group had dispersed, but Dustin was walking alongside the teacher as they headed out the door. His body language was troubling—walking too close to Ben, bumping into his side, talking, his face animated. The teacher was attentive, two short men eye-to-eye, but he kept pulling back, trying to put some distance between them. It resembled a skit from a high-school performance, but there was nothing humorous about it—something serious was being said.

“What in God’s name?” Hank muttered.

“But something is wrong, Hank.”

We watched the two disappear out the doorway.

Bothered for that moment, I put it out of my mind until two weeks before the finals and the Christmas break. I’d been sitting in the adjunct faculty office, reading student term papers and then quietly reviewing a fraud case for Aetna Insurance, my mind numb with the banality of white-collar crime, when I decided to head home. Seven p.m., the late-afternoon classes ended, students swarming into the dark wintry night—headed back to dorms or to cold cars in the lot. I waited until the hallways were clear, then wrapped a scarf around my neck, grabbed my gloves, and walked out of Charlton Hall.

Raised voices stopped me. At the end of a wing of faculty offices a door swung open, slammed back. Ben Winslow’s office, I knew. At first I saw no one, but immediately I recognized the voice: Dustin Trang.

His words shrill, panicked. “You promised.”

Winslow’s answer. “I can’t keep a promise like that.”

The sound of a book slammed to the floor. A hand banging a wall.

Dustin’s voice broke. “You said you were my friend. You acted…”

Winslow spoke over Dustin’s words, hurried. “C’mon, Dustin. Listen. I told you…”

Suddenly Dustin stepped out of the office but faced in. From where I stood I could see his purplish face, his spiky hair sticking up, his fists raised in the air. “You promised…”

“You gotta believe me, Dustin. This is…wrong.”

Dustin cuffed his ears. “It isn’t. It isn’t.” Then, his voice lowering, “I’m sorry I told you.”

“But you did.”

Silence as Dustin breathed deeply. “I lied, Professor. I made it all up.”

Winslow appeared in the doorway. The small, round man with the fuzzy hair appeared tense, his reddish skin now blanched. He pointed a finger into Dustin’s chest. “I have no choice.”

“But you promised.”

“Stop saying that.”

Dustin backed up, then stamped his foot. “You could get in trouble, Professor.”

“No, you could get in real trouble. The cops.”

A long, drawn-out, “Noooo.”

Dustin spun around, his fist in the air, and suddenly he slammed his book bag against the wall. “Damn it all.”

Ben approached him, but Dustin held up his hand, traffic-cop style, and Ben froze. Ben slammed his office door behind him, leaned against the hallway wall. His voice roared: “Damn, damn, damn.”

A few students, walking out of other faculty offices, had bunched in a corner, watching and whispering. One, grinning, held up his cellphone and was recording the quick encounter.

Dustin stormed away, giving the finger to the kid with the cellphone, and came face to face with me. For a second he paused, deliberated what to do, then caught his breath. A weird smile covered his face as he rushed by me.

An office door swung open, and Professor Laramie stood in the doorway, his arms crossed over his chest. He frowned at Ben, who ignored him. He was a small, wiry guy I’d never liked—and an avowed enemy of Ben Winslow’s out-there politics. I’d sat at faculty meetings and listened to Laramie and Winslow go at it, their dialogue mean-spirited. Laramie was notorious for standing outside Winslow’s classroom, jotting down suspect remarks and forwarding them to Academia Fact Check, a right-wing alarmist group convinced professors were poisoning the minds of American youth. Winslow was his main topic—which Winslow relished. Indeed, when the shadow of Laramie lingered in the hallway, he upped his sensational remarks.

Now as I passed Laramie, I stared into his face.

“You find this funny?” I asked bluntly.

Surprised by my words, he shot back, “Nothing is funny that comes out of that madman’s office.”

“You have a grin on your face.”

“It’s not a grin, Mr. Lam.”

“What would you call it then?”

He watched me closely. “Did you ever read Hawthorne? The Scarlet L

etter? Chillingworth. It’s the look Satan has when he knows he’s checked another soul into hell.”

“And you’re Satan?”

“God, no. I work for the opposing team.”

Chapter Two

At six o’clock on a Thursday night Zeke’s Olde Tavern, down the street from my apartment off Main Street in Farmington, had a used-up feel to it. The barmaid dragged a grimy cloth over old oak tables, and the bartender polished glasses so scratched I was certain bacteria smiled back, taunting him. Nearly empty—my favorite time of the day there—Zeke’s was established in 1907, according to the sign outside, which no one believed. Some recall another sign, blown away by Hurricane Carol back in the fifties, that said, simply: c.1900. No one believed that either.

Sometimes beautiful young girls in finishing school dresses from nearby Miss Porter’s School peered into the window as they strolled into town, but the place was too Dante’s Inferno for delicate minds.

Sitting at a back table, I was talking about the encounter—Dustin Trang and Ben Winslow, a scene that still shocked me. I shivered in the drafty room. Munching on a burnt hamburger and sipping a tepid Sam Adams, I brought Hank Nguyen, now in street clothes, and Liz Sanburn, my ex-wife from my Manhattan days, now a psychologist with the Farmington Police, up to speed.

“Rick, you gotta be kidding.” Hank narrowed his eyes. “Dustin is…shy. I can’t imagine him fighting with anyone.”

Liz sipped her glass of wine. “Rick, why are we talking about this student?”

“I can’t get him out of my mind. He was so belligerent.” I took a sip of beer. “It wasn’t pretty.”

Hank leaned on the table, “I know what you mean about him—it bothers me. He looks so…lost at the college.”

“I wonder how he ended up there.”

Hank grinned at me. “I got some answers. In one of my feeble interrogations—friendly, I might add—I learned a little about him. He lives in a housing project with his family. He’s from the next town over—Bristol.”

I raised my eyebrows. “But Farmington College?”

Hank nodded. “A scholarship from the Bristol Lions Club or the Rotarians. Some civic group. He’s a half-time student, works days at a dairy bar restaurant on Terryville Avenue near his home, drives over for two or three classes. A freshman.”

“A smart kid?”

“Yeah, that’s the thing. Not talkative, but comes off as real bright. A few offhand remarks—clever. But afraid of his own shadow and with that oddball behavior.”

Liz had been quietly listening.“If I can add my two cents’ worth—though as a psychologist I should charge you for the advice—maybe he’s insecure there. Farmington College is another world from hardscrabble Bristol.”

“Maybe,” I answered. “Still, we’ve got lots of scholarship kids.” I shook my head. “I’ve watched him in the hallways. There’s anger in him. And that’s what I saw when he confronted Ben Winslow.”

“But it sounds to me that Ben was also angry,” Liz said. “You said he was fighting back.” Her eyes got cloudy. “And that doesn’t sound like the Ben we know.”

I tapped my fingers on the table. “Something nasty is going on. True, I didn’t expect it from Dustin, though I don’t know him. But students don’t talk like that to professors. They…”

Hank interrupted, his eyes flashing. “I was always tempted to.”

“Yeah, I remember.” I pointed a finger at him. “But this smacked of some deep-seated disagreement—something personal.”

Liz sat back, tilted her head. “Are you sure you’re not reading too much into this, Rick?” She was wearing dangling emerald earrings that caught the overhead fluorescent light. Ex-wife or not, I often found myself staring at her beautiful face, that alabaster skin setting off her dark eyes. A woman in her forties now, our failed marriage years in the past from student days at Columbia, she often caught me looking. Stop that, Rick. A look that said: Sometimes I think you think we’re still in love.

We were.

“But I was also surprised by Ben,” I went on. “The friendly professor that everyone loves.”

Suddenly Liz sat up. “That reminds me of something Sophia said about Ben being rattled. Just the last few days or so.”

“Sophia? What? Tell me.”

“My, my.” Liz’s eyes twinkled. “The once and future investigator.”

Sophia Grecko, Liz’s friend, was an instructor in Art History at the college, a fiftyish widow who’d been dating the divorced older Ben Winslow for a few years. Ben lived on the first floor of a triple-decker apartment house in Unionville, while Sophia occupied the second floor. We’d socialized with them a few times. A melodramatic woman who often got on my nerves—“Call me Natasha,” she’d warble after too much wine one night—she wore thick makeup to cover up a pocked face and skintight knit dresses that made male students trail after her through the hallways. Liz always told me I was narrow-minded. She defended her. “She’s warm and funny and—my friend.”

Ben Winslow, the ragtag hippie professor who resembled an unmade bed, was smitten with her. The unlikely couple lingered over cocktails on a Friday night at the local Applebee’s while a piano player sang an anemic version of “The Way We Were.” I know this because, unfortunately, Liz and I were sitting at the same table.

“Tell me.”

“I really didn’t pay it much attention. We were talking about our little get-together this coming weekend to celebrate Ben’s new book, and she said Ben didn’t seem interested.”

“Maybe the end of the semester. Christmas almost here. Term papers…”

She shook her head. “No, not that. Overnight Ben has become secretive. He hides away in his home office—mumbled conversations on the phone when she comes near. When she asked him why he was so distracted, he wouldn’t answer.”

Hank was anxious to talk. “Do you think it has to do with Dustin?”

“A little far-fetched.” But I hesitated. “Who knows? Ben does get involved with his students’ lives. They run to him with their problems. Sort of a campus legend.”

Liz smirked. “Campus legend, indeed. Getting involved with students got him a divorce a century back, no?”

“What’s that?” Hank was curious.

She leaned in. “A stupid half-second romance with a teaching intern from the UConn School of Social Work, some blushing co-ed who charmed the craggy professor.”

“Illegal,” Hank said in his state-cop voice.

I made a shocked face. “Not back then, Hank. No one cared who slept with who back then, especially in hushed, ivied halls. We’ve added a few more academic felonies to the ledger since then.”

“I don’t think peace activist Ben is wooing little goofy Dustin,” Hank said.

“Agreed, but something is going on.”

“Since I’ve been on campus,” Hank was saying, “I’ve been talking to a kid named Vinh Thanh Luong, aka Brandon Vinh, who’s in my seminar. He’s a part of this Asian-American Alliance at the college, a social club, I guess.”

“Yeah,” I broke in, “I’ve seen him around campus. Back-slapping, in-your-face politician.”

“Not a favorite of mine. All buddy buddy—but arrogant. He’s seen me—even you that one time—talking to Dustin in the College Union.”

“And that’s a problem?”

Hank rushed his words. “He has it in for Dustin. Brandon is a sort of jock, a muscle-bound loudmouth student who talks too much in class.”

“BMOC,” I said. “He swaggers.”

“That’s his only gait,” Hank laughed.

“Where are you going with this, Hank?” Liz asked.

“Well, Brandon wants to be a cop, which will never happen. Too gun happy in a mindless hey-anybody-see-my-Colt-45?-I-left-it-somewhere-duh way. If you know what I mean. Anyway, when he spotted Dustin on campus back in September h

e approached him. Vietnamese to Vietnamese. Heartwarming, right? Strangers in a strange land. Dustin rebuffed him, and pretty rudely.”

“So?” I took a swig of my beer. “He rebuffs everyone.”

Hank waved a hand in the air. “Brandon didn’t like it. So Dustin has an enemy. But what I’m trying to say is that Brandon said something strange to me. I was telling him that he should encourage Dustin to come to Asian-American club meetings—Brandon’s pet project—and he said ‘No way.’”

“A real democratic soul.” From Liz.

“No, he told me. No. Capital N-O.” Hank stressed the word. “Me, the state trooper, yes. Honored guest.” Hank bowed. “Then, Brandon said, ‘You know, Officer Nguyen, that kid is gonna murder somebody someday.’”

“Christ, what did you say?”

“I told him he talks too much.”

***

Ben Winslow was standing at a vending machine at the end of the hallway, staring blankly at the glass. His hand clutched a dollar bill, but he seemed frozen. When I approached him from behind and called out his name, he jumped, spun around, dropped the bill onto the floor and then, shuffling, stepped on it.

“Sorry, Ben. I didn’t mean to startle you.” I smiled at him. “Such concentration on the choice of a candy bar.”

A blank stare. “What?” Then he snapped out of it. “I don’t even eat candy.”

He stepped back, ignoring the crumpled dollar bill, but I stooped to retrieve it. “Here.” He stared at my palm.

A weak smile. “Thanks.”

“Everything all right?”

“Yeah. Of course.” An edge to his voice. “Why wouldn’t it be?”

“Saturday night still on at your place? Liz mentioned…”

He broke into my words. “I guess. Sophia wants to celebrate my book.”

“It’s an event.”

“I guess.” He gazed over my shoulder.

I stepped closer. “What’s the matter, Ben?”

He shook his head absently. “A lot on my mind.”

“Wanna talk about it?”

Child of My Winter

Child of My Winter No Good to Cry

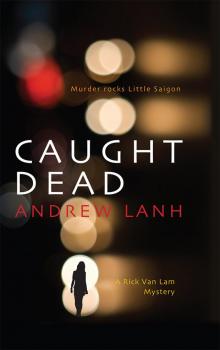

No Good to Cry Caught Dead

Caught Dead Return to Dust

Return to Dust