- Home

- Andrew Lanh

Return to Dust Page 3

Return to Dust Read online

Page 3

“Was Davey upset?”

She waited, her finger rimming the espresso cup. “You’ll have to ask him that.”

“I will.”

For the first time she smiled. “Then you’ll take the case?”

I didn’t answer. I took out my wallet, withdrew some cash, and slapped some fives on the table. Immediately she reached into a pocket. “We’ll split it, okay?” She pushed back some of my money, and I picked it up, tucking it into my shirt pocket.

I wasn’t through yet. “Karen, there’s one thing that’s the bottom line. Motive. You say murder. I say motive. Who’d want your aunt dead? The spats you talk about are…trivial. Motive? Help me out.”

She closed her eyes for a second. “I can’t. My aunt was a simple woman. She cleaned houses, for God’s sake. Even yours. She went on trips and cruises with her friend Hattie. She went to the Indian casinos. You know, Foxwoods. She had friends, she went to church. She adored church. She had no enemies.” A pause. “I mean, yes, sometimes she could be curt, rub folks the wrong way.”

“But somebody killed her?”

She reached over to tap my wrist. “Look, Rick, do this for me. I need a professional eye here. Just look into it for three weeks or four. Promise me that. If, after that time, you tell me it was suicide, I stop. Okay. Okay?”

Suddenly, unexpectedly, she took a check from her pocket and handed it to me. She’d already made it out.

“I don’t know anything about rates but this is a down payment, I guess. A retainer? Use what you need to for three weeks or so, and then, if there’s anything left, give it back. Okay?”

She handed me the check for five thousand.

I grinned. “My rates are considerably lower.”

“Perhaps you should think about that.”

“All right.”

I told her about my usual rates, about the contract I’d want her to sign, other legal ramifications, and the reports I’d file with her periodically. She nodded through it all, but she’d stopped listening. She’d gotten what she wanted.

“Don’t count on anything.” I stood up. “I have to tell you that up front.”

For the first time she grinned widely, her face bright and sunny. She reached out and touched my sleeve—a casual, uncomplicated touch that I felt through the fabric of the sports jacket I wore.

“I owe her something, Rick,” Karen confided. “She raised us. I didn’t like her a lot of the time, but I did love her. When my parents died, she was the one who watched over me. Now I have to watch over her. It’s something left undone in her life. I have to do it.”

I nodded.

Karen’s face got cloudy. “Somebody didn’t love her. Somebody killed her.”

Chapter Three

As I trudged home through leaf-strewn sidewalks, a wispy autumn drizzle made my skin clammy. Fall is my favorite season, but I don’t like it when the skies open up. The clever, seasoned PI who didn’t check his phone for a weather update. The detective strolling without an umbrella. By the time I got home, I was wet.

I smiled as I recalled words from the little book I carried to America, a tattered volume that once belonged to my mother. The words sometimes came to me unexpectedly, sometimes like my own private jester. Buddha’s words are a large cloud. The rain it gives waters the world.

It didn’t matter because I was still soaked.

I live on Cedar Lane, a quiet street running off Main, maple-shaded and elegant, lined with Victorian gingerbread houses, huge places that evoked days when families were large and played croquet on rolling green lawns. I’m down the street from Miss Porter’s School for Girls, the exclusive prep school whose buildings resemble the expensive old homes but with a lot more children, most of them teenage girls with trust fund personalities. My apartment is on the second floor of a wonderful painted lady. Rococo turns and surprising angles, and floor-to-ceiling bay windows with rippled glass panes. Gracie, my landlady, paints the house canary yellow each spring, each season the color a little more shrill. “The cheap blonde on the corner,” some folks mocked. I like that. Back home, I changed my wet clothes, lay on the sofa, and stared out into the backyard where the giant oak trees sagged under a wet El Greco sky.

Later I called Liz Sanburn, a criminal psychologist working out of the Farmington Police District. She’s also my ex-wife.

She was in her office.

“Sanburn,” she said, all business.

I smiled. Her whiskey voice, throaty and low, was so different from Karen’s reedy, high-pitched tone. Liz is dark-complected, as slender as Karen perhaps, but athletic, the result of those dedicated aerobic classes at the West Side Y way back when. Her dark raven hair is always close-cropped, hugging her head like a bonnet. That’s so the elegant gold-and-diamond earrings she favors stand out, dramatically.

I stopped myself—why this comparison of the two women?

“Liz, it’s Rick.”

I could hear the smile. “Oh, no, either you need information from the police or you’re asking me out to our ritualistic and obligatory ex-wife-meet-ex-hubby dinner.”

I hesitated. “Actually, both.”

“I knew it. I was looking at the calendar and expecting your call. You are a rigid type, Rick.”

“The good nuns drilled obedience into me.”

“Not always a virtue.”

“It makes my vices predictable.”

“But there are just too many to count.”

“We can start over dinner tonight.”

“What do you need—besides a dose of atonement for sins committed?”

I told her what I wanted—a copy of the Farmington Police report on Marta Kowalski’s death. A copy of the autopsy. Any toxicology or serology reports. The usual. I could get them using the circuitous channels of my employer, Gaddy Associates, but Liz is more thorough. She has a veteran detective’s research eye. If there was anything else in the files—or anything said informally in the office when she searched out Marta’s file—she’d pursue it. She understood the importance of the offbeat suggestion, the random bit of information. She’s also a wonderful gossip, though she’d deny it. Gossip, she once told me, is not gossip when it’s fact. Then it’s information.

“Yeah,” I’d told her then, “that’s why you subscribe to The National Inquirer.”

She’s worked with me often enough to understand that trivial detail—albeit dismissed by the police clerk—might solve a crime. She also knows that police stop looking for evidence when they’ve made up their minds. And having categorized Marta’s death a suicide, there was no need to continue looking.

“Be nice to me,” I teased.

“I’m always nice.”

***

Until dinnertime I caught up on paperwork, did some billing on some completed fraud cases, and began a file on Marta on my Mac laptop, where I store my research and notes. I created a new file under Marta’s name and jotted notes about the case. I had little except Karen’s name and her earnestness, as well as a notation about brother Davey’s anger and alienation from his dead aunt.

I dressed for dinner with Liz, donning iron-pressed khaki slacks, a pinstripe tan shirt with an art deco-design tie, and a mustard-yellow sports jacket, finished off with tasseled oxblood loafers. I carried a tan London Fog over my arm.

My look for fall—I looked like a tree waiting for winter.

I knew my clothes made my mocha skin seem even darker and my black hair looked like India ink. My deep blue eyes, a gift from the American soldier who was my father, were lost in the dark face inherited from my Vietnamese mother. I’m a good-looking guy, I know—sort of a vain declaration. But women find me attractive. My slanted lazy eyes can widen suddenly to reveal deep baby blue pupils. People don’t expect such eyes, aquamarine and glittery, from an Asian.

My mind wandered to Karen Corcoran. What did she see w

hen she looked at me?

Liz and I met in the parking lot of Cavey’s, a classy French restaurant we both like in Manchester by way of I-84. She stepped out of her car and I kissed her on the cheek. She was dressed in a brocaded jacket, vaguely Chinese, a silky brown and lavender mix of shades. She shivered as a slight breeze blew across the parking lot, and she rushed toward the restaurant. She looked over her shoulder and saw me staring. “Shame on you.”

We had a curious relationship, the two of us—one we both cherished but…at times difficult.

We’d been married in Manhattan right after Columbia College, and by the time I’d joined the NYPD, our marriage was already crumbling. Three years later, when I left the force and headed to Connecticut, it was over because we couldn’t live together. Somehow, though, our love refused to die, and she followed me to Connecticut. She said she needed to be near me—not married, God no, but near. The stupid fights, the late-night phone calls, the awful silences, the explosive angers—led to a necessary friendship that most folks would never understand. Sometimes we dreamed of reconciliation, but it never happened. We always found each other when the loneliness set in. Then, suddenly, we remembered that we were divorced. I can’t imagine a life without her.

Seated, we made small talk until our drinks arrived. Then she became all business, dipping into her purse and extracting a thin sheaf of folded computer print-outs. She spread them out on the table, leaned back, took a sip of her martini.

“It’s pretty cut and dried.” She slid the sheets toward me. “I don’t know whether there’s a murder lurking in these pages.”

“Simple suicide?”

“On the night of October 11, around six in the evening, Marta Kowalski called Richard Wilcox, an old friend, to tell him she planned on visiting. He says she was depressed on the phone—crying, incoherent. Wilcox lives in a condo complex less than a half-mile from her house, and she said she’d walk over. She always walked to his house. When she didn’t show up, he called and got no answer. The next morning some school kids spotted her body on a rock ledge in the Farmington River. The police suspect she’d jumped off the bridge on the walk to Wilcox’s. It’s out of the way, out of sight, banked by overhanging hemlocks. The kids screamed until someone called 911. It’s not a huge drop but she broke her neck, smashed a shoulder. Enough of a drop to kill, I guess.”

“Nightmares for those kids.”

Liz thumbed the report. “That’s all the info that’s in here.”

“Any evidence of foul play?” I picked up one of the sheets and ran my fingers down it, rereading what she’d just summarized.

“Not in the report. Everybody keeps saying how depressed she was. I mean—Karen. Wilcox. Others. No one thought to get the old woman counseling. Christ, these people.”

I smiled. “Spoken like a true police psychologist.”

“That’s why they pay me,” she shot back, a little irritated.

“Sorry.” I waited until she smiled at me. “So everything points to it being a simple suicide. She walks over a bridge high enough for death and is swamped by a wave of despair. She hurls herself over the railing.”

Liz nodded. “Well, that’s how the police read the facts.” She drummed her fingers on the table. “So Karen thinks it’s murder?”

“Marta had tickets for Vegas three weeks later.”

Liz frowned. “So what?”

“I know, I know, but when you’re a family member…”

“I never thought that Karen was all that close to her.”

That surprised me. “You know Karen?”

“We’re in the same health club. Once or twice we chitchatted. That kind of thing. She mentioned her aunt one time to a bunch of us in the sauna, and it wasn’t flattering.”

Now I was interested. “What did she say?”

“Oh, I don’t know—something about another boring lunch with her. A throwaway remark, but she said it sarcastically. When we all laughed, she said she was sorry—it came out wrong, she said. She babbled, apologetic. Sort of embarrassed, like she couldn’t stop talking.”

“That all?”

“That’s it.”

“The autopsy?” I prompted.

“Healthy older woman, in pretty good shape, a little overweight. Nothing out of the ordinary. Except one surprising thing, though maybe it wasn’t so surprising—in retrospect. Marta had an alcohol blood count twice the legal limit. For driving. Of course, she wasn’t driving. She was a little bit hammered as she toppled to her inglorious death.” Smiling, she took a dramatic sip of her martini and raised the glass to me.

“Karen didn’t tell me that.”

“Maybe Karen doesn’t know.”

“She must.”

Methodically I rustled through the sheets while Liz scanned the menu, holding it close to her face. Vanity, I thought, smiling. Her reading glasses remained in the purse. She ordered for both of us, while I kept nodding at her suggestions. She knew what I liked. I wanted to read everything she’d brought, but it was as she said. The only new information was Marta’s intoxication, but I figured if you’re depressed, that’s an easy and comfortable route to take. Numb all the available senses.

“Could she have toppled to her death? Not a suicide but a simple accident?”

“That’s in there somewhere.” Liz touched the report. “The police ruled that out because the railing is too high to simply topple over. You have to climb up a stone partition to get over. And even then—a shallow rockbed below. That would sober me up fast.” She frowned. “I can’t see this leading anywhere.”

“Karen wants me to give it a month.”

She shrugged her shoulders. I knew the gesture—it’s your call.

“Something else,” Liz began. She bit her lip.

“What?”

“Do you know Vuong Ky Do? Willie Do?”

“Yeah, sort of. He used to work at the college. Why?”

“Vietnamese?”

I nodded. “Yes.”

“Back in April Marta called the cops on him. I guess they’d had a fight in Joshua Jennings’ front yard. She claimed he didn’t say anything, but glared at her. Her word—glared, so much so that she felt in danger.”

“He’s an old, harmless man.”

“Are you sure?”

“No, I’m not. I mean, he’s been scarred by the war, a man who always looks hurt. Frozen men, I always call such men, but…”

She broke in. “The cops went to his home just as a precaution. Marta said nothing happened, but they wanted his side. He had no side. When the cops questioned him. he folded in, started to shake. He stared—a rock. His son rushed in. It went nowhere. Marta, I gather, had yelled at him for tracking dirt onto Joshua Jennings’ floor—she’d just polished it. A war of words—from her side. No follow-up.”

“I can’t imagine Willie doing her harm.”

“I don’t know the man.”

“Well, neither do I, but…” My voice trailed off. “I’ll talk to him.”

Liz didn’t look happy. “I hesitated telling you. I know your place in the Vietnamese community is tenuous.”

“I’m fine.”

“Now you’re lying to me.”

I grinned. “How can you tell?”

“Please, dear Rick. You’re as transparent as a boy stealing apples from a farmer’s yard.”

I sat back. “Willie Do.”

Do Ky Vuong. A casualty of the old war. Stunned by pain.

The few times I thought about Do Ky Vuong—the man everyone called Willie Do—I found myself suddenly back in old Saigon, trapped in a memory of my friend Vu’s father, Tranh Xan Tan, the frozen man so traumatized by the Commie re-education camp. Two similar men who rarely spoke, but worse—men whose ravaged faces communicated all the horror of that war and punishment—the hollow eyes, the blank stare, the voice so soft it m

ight be one you imagined. The shell of a man. The man whose face was a clock without hands.

I trembled, remembering.

***

I first met Willie Do at Farmington College, where he worked as a janitor. Spotting him as a fellow Vietnamese, though one who hugged the corners, I’d approached him, introduced myself, but was met with silence. Soon I learned that his reticence was more than his dislike of me—the mixed-blood bui doi on campus—though that was part of it, perhaps. But Willie Do turned away from everyone. It was as though someone plopped him down into an American landscape, and he awoke to nightmare and fear.

He even looked like my boyhood friend Vu’s father—smallish, tight-muscled, wiry, hair clipped off with kitchen scissors, a work shirt too large for his tiny frame. I’d learned through my young friend Hank Nguyen, someone who had his ear to the Vietnamese tom-tom drums, that he’d been re-educated—a beaten man who escaped with his wife and son and daughter to Hong Kong—and then on to Guam and the States. His little daughter had been raped and brutalized by Thai pirates before his eyes, and she died weeks later in a Hong Kong refugee camp. His vow of silence settled in, horrible, inviolable.

Hired by Goodwill Industries, set up in a small apartment in Unionville, he drifted from one menial job to the next until Farmington College hired him. But shortly after I began working there, he was fired. He chain-smoked Lucky Strikes, inside in winter, in the hallways. Warned over and over, baffled by such a law when utter lawlessness had earlier defined his life, he persisted—until he was let go.

He did handyman jobs around town. A car washer, trash man. And he was Joshua Jennings’ twice-a-week yardman.

How did he connect to the story of Marta Kowalski?

“Rick, your mind is wandering.”

“I’m thinking of Willie Do.”

“I know.”

Over dessert we caught up on each other’s lives. She’d been back to New York to visit her parents who were still angry she’d left the city. In the warm light of the candles her olive-toned skin looked muted, silky. She was the dark negative to Karen’s sunny photograph. If I hadn’t been married to her once already, I might have been tempted.

Child of My Winter

Child of My Winter No Good to Cry

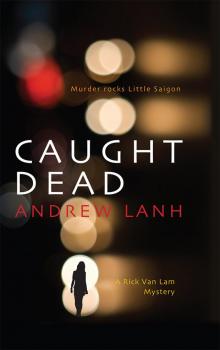

No Good to Cry Caught Dead

Caught Dead Return to Dust

Return to Dust