- Home

- Andrew Lanh

Child of My Winter Page 4

Child of My Winter Read online

Page 4

The deliveryman had stumbled on the porch steps, and we’d heard his thick subcontinent accent, “Sir, pardon please, but a porch light would help.” To which Ben answered, “The bulb is out and the landlord lives in Brooklyn.”

Watching Ben’s silhouette as he concentrated on arranging the food, I felt quickness in my chest—something else was going on. My gut brought me back to Dustin Trang and that explosive scene in the hallway. Ben’s battles royal with his children were the stuff of routine and, according to Marcie, he’d reconciled himself to periodic skirmishes in the name of love. No, this was different. He looked marrow-deep sad.

The conversation over dinner meandered through academic politics, always petty and familiar old territory, to Ben’s new book, stacks of which were precariously piled on a sideboard. “The solitary item in a goodie bag for each of you,” Sophia joked.

Ben quietly watched her, warmth in his eyes. When Sophia lapsed into silence, he began rambling about the field research his grad students were working on, no doubt spurred by his own obsession with tent-revival religion. He talked of a young woman who spent some time in Middletown at a charismatic Catholic church, a squirrely sect that published diatribes each Saturday in the Hartford Courant, messages from the Virgin Mary that were unfortunately ungrammatical. “I’d recommend her to an ESL class,” Marcie noted.

The only person who didn’t laugh was Ben, sitting with his arms folded over his chest and observing our banter with slatted eyes, looking unhappy.

I plunged in. “Ben, I remember hearing you praise Dustin Trang’s paper on the Great Awakening—”

I stopped, so fiery was his glare.

Liz probed, “What in the world? What are we talking about?”

Ben hissed, “Very good, Rick. I was waiting for you to bring him up.” He paused, but faltered. “I mean, yes, that boy has a wonderful mind, his paper was amazing, a personal slant because his family is mired in some cockeyed mixture of evangelical Buddhist Protestantism, whatever that is.”

I was confused. “But that scene in the hallway…”

“Nothing. Nothing at all.”

But I’d ruined the evening, if I could judge by the censorious—if baffled—glances heaped upon me by Marcie and Liz. I’d broached a forbidden topic, taboo among the remnants of tikka masala on the stained tablecloth.

So the evening stumbled to an end as we moved back into the den where Sophia, rattled by the shift in tone, cut enormous slabs of her chocolate cake. We drank tea and ate cake and waited for the clock in the dining room to announce ten o’clock and our polite departures.

A sudden rapping on the front door made us jump. Sophia let out a throaty bark that made Marcie giggle. I checked my wristwatch. Nearly ten.

With a quick glance at Ben, Sophia rushed to the front door and quietly pulled back the curtain to peek out. Facing Ben, she mouthed a word: Student.

“At this hour?” Ben wondered out loud. He stood up.

Sophia was unhappy. “You have to stop letting your students know where you live. This isn’t the College Union, Ben.”

Walking to the window, Ben was muttering. “Nobody should be here. You know I don’t invite students…” Stepping around Sophia, he pulled back the curtain, pressed his face against the glass, and gasped.

I moved behind him, strained to look out onto the dark porch.

A slight, shadowy figure rapped again, insistent, then stepped back to the edge of the porch and waited, rocking back and forth. Bundled up in a hooded parka, a thick scarf wrapped around his neck, he seemed a short jittery snowman.

His face reddening, Ben pulled open the door, although I reached around him to stop him. Too late. A flood of light flooded the porch, and Ben and I stared into the trembling, frozen face of Dustin Trang. Of course, he’d expected to see Ben, but his eyes popped as they flew to my face, and he stumbled backward.

“I told you, I told you…” Backing up, he collided with the balustrade, spun around like an out-of-control wind-up toy, and staggered down the steps, running lopsidedly until he disappeared from view.

“Ben,” I pleaded, “what aren’t you telling us?”

“None of your business.”

Chapter Four

Brandon Vinh sat with Hank in the cafeteria late in the afternoon, that hollow time when few students hung around. Three other Asian students clustered around him as he spoke. One young woman, maybe Korean, leaned into Hank, the uniformed cop at leisure. She was ignoring Brandon whose words dominated, and Brandon wasn’t happy at this impromptu meeting of the Asian-American Alliance, a small group lately energized by Hank’s recent appearance on campus.

Hank waved me over.

A Criminal Justice major who’d never taken any of my night classes—I was convinced he purposely avoided me, although I had no proof—Brandon was the loudest member of the seminar Hank was mentoring. Hank had told me Brandon’s goal was the FBI. Quantico or bust. Terrorist underground activity. Homegrown wacko jobs from Oklahoma. To carry a gun twenty-four/seven. Hank had recounted this one night in a wary voice. “Dead-end dreamer,” he’d finished. “Imagine him with a gun.”

I sat down facing Brandon. He unlocked his hands from behind his head, crossed his arms, and watched me with questioning eyes. When Hank began speaking, he broke in. “We’re talking about our end-of-semester Christmas get-together at The Silo down the street. This Thursday after the seminar. At seven. You wanna come, Prof?” His smile was not inviting.

“Maybe.”

Hank cut in. “Of course Rick’s invited.”

Brandon was all business. “We got twelve people committed. Check the invite on Facebook, gang. I arranged it.”

The other students shuffled papers, mumbled about obligations, stretched out arms, one young man crumpling his Coke can as he narrowed his eyes at Brandon. Smiling at Hank and even at me, they left the table, but Brandon stayed, jotting some notes into an iPad he balanced in his lap. Leaning back, Hank watched him, though occasionally he glanced at me. I knew Hank well enough to read his irritation—his dislike—but I also understood that, curiously, he was enjoying this.

“You don’t take Rick’s classes?” he asked Brandon.

Brandon contemplated me as he rocked in his seat. “Rumor has it he’s too hard a grader.”

“You don’t like a challenge?” I said.

“I like to pick my battles.”

“Are we done here?” Hank reached for his jacket.

“A minute, okay?” I faced Brandon. “Could I talk to you about something that’s bothering me?”

Brandon sat up, his face brightening. His long legs stretched out under the table, the tips of his expensive Timberland boots visible. A junior at the college. I’d read his bio in the campus newspaper. Campus leader—and the noisiest student in the quad. Lacrosse captain. Varsity tennis. In some ways he reminded me of Hank as a young student: tall, confident, self-assured. But Brandon lacked Hank’s…not softness, but kindness. Maybe humanity is the word I’m searching for. The obligatory Criminal Justice buzz cut inherited from the Eisenhower years no student remembered gave him a look that exaggerated his larger-than life ears. A smallish head that perhaps wasn’t that small but Brandon, a weightlifter, had broad shoulders and a thick upper chest on that frame. In the middle of December he wore a sleeveless muscle shirt.

I watched him closely. “Perhaps an unethical talk.”

He grinned. “Even better.”

Hank was bewildered. “Rick, what?”

“Dustin Trang,” I said in a flat voice. “Anh Ky Trang.”

Brandon’s face closed up. He pulled his legs back from under the table and sat up straight. “Yeah? What?”

“A comment you made about him.”

He glanced at Hank. “You squealing on me, Officer?”

Hank shrugged, glaring back. “Maybe you should be more careful when y

ou talk to cops.”

Brandon grinned widely, performed a half-bow.

I wasn’t buying it. “I’d like you to tell me why you said what you said about Dustin.”

“Little Anh?”

“Same person.” I waited. “You said he’d kill somebody someday.”

“I said that?”

“Yeah. That’s sort of hard to forget, especially if you’re talking to a cop.”

“All right, all right. Who the hell cares?” His eyes accused Hank. “I was just talking, you know.” A little nervous now, a bead of sweat on his brow that he brushed away with the back of his hand.

“Tell me.”

Hank tapped his finger on the table. “Yes, Brandon, tell us.” He started playing with his empty Styrofoam cup, rolling it around in his fingers.

“I don’t like him. That’s all.”

“Why?”

“Have you seen him? Christ, the way he dresses. Those shiny cheap jeans from Walmart, rolled up to his knee, baggy at his ass, a spiky haircut you wouldn’t give to a boy you hated.”

Hank tapped the cup on the table. “He’s poor.”

“He’s odd. When he first came here—God, I was surprised they let in a dumb scholarship kid like that—I walked up and said hello. I mean, I knew who he was—knew about his family. He shrugged me away.” He spoke through clenched teeth. “A bastard.” He caught his breath. “I mean…”

Bastard. Bui doi. A dangerous word in his community. In my community. My mother. My father.

“Brandon…” Hank cautioned.

“Hey, I’m sorry.” But he laughed nervously. “What the fuck.”

“Look,” I said, “I’m worried about him. I witnessed a scary scene with Professor Winslow.”

Brandon waved his hand in the air. “Yeah, like everyone talks about that. It started a couple days back—out of nowhere. Some asshole shot the fight and uploaded it onto YouTube. With funny comments. ‘The Geek and the Prof, Round One.’ Here’s this pipsqueak kid, who never opens his mouth in class. Like he knows he doesn’t belong here. But suddenly he’s in the hallway yelling at the professor, threatening. It’s like—like Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde. You know, this inner demon coming out.”

I broke in. “What started it?”

He shrugged. “Dunno. Somebody in the Alliance—I’m chairman, by the way, my idea a year back—anyway, this kid, a Chinese exchange student—he told me the professor asked him a question in class he didn’t like. I mean, Professor Winslow’s got a rep as a softie—everyone goes to him to solve problems. Easy A. You can cry on his shoulder, they say.”

“That seems a little preposterous,” Hank interjected. “You don’t flip out over and over because of that.”

“Yeah, true. Maybe you get mad at a prof, but you don’t bang on his office door and bay at the moon. Jesus Christ! They tell me he did it again. Today. Real loud. He’s weird. What can I say? If you’re a goddamn nut, and certifiable—look at him—then the slightest thing can set you off.”

I sat back, considered his words. “It has to be more than that.”

Brandon eyed me curiously. “Why do you even care?”

I held his stare. “Why don’t you care?”

“It’s not my business.”

Mind your own business. Echoes in the college hallway. Ben hissing at me.

Hank’s voice got brittle. “Brandon, for God’s sake. A little decency, no? What do you know about his background?”

“That’s the trouble, Officer Nguyen. I know too much about his background. More than I want to know. Bristol, that stinking hellhole.”

“So you know his family?”

“By reputation. Ba-a-a-a-d reputation.”

“Tell us.”

He surveyed the room and nodded at a young woman passing by. She debated walking toward us, but Brandon purposely swiveled his body away, leaning into me. “In a world of success, I mean, Asian success, you know the children of the starving boat people going to Harvard and buying vowels on Wheel of Fortune—hey, the Trang family slipped a notch on the old wheel of fortune. Worse, because they were programmed for American dreaming.”

“I don’t follow this,” I said.

Hank’s voice was sharp. “Dustin is a college student. That says something, doesn’t it?”

Frustrated, Brandon assumed the manner of someone compelled to blab an unpleasant truth he’d rather not—but secretly relished it. “They’re dirt poor because all they do is dream.” He let that sink in. “The Vietnamese community in town, small though it is, twenty or thirty families, is close-knit, you know. Families that are…joyously middle-class. Maybe upper middle-class. Proud of it—we wear it when we cruise around in our BMWs. My father escaped by way of Thailand at the end of the eighties, met my mother at Fort Pendleton, had a cousin down here, ran a grocery. Now we own two gas stations, a dollar-value convenience shop, a laundromat.” He sat back, beamed. “Money for nothing, chicks for free.”

“What?” From Hank, irritated.

“Pop music gives me my lines.”

Hank scowled at him. “Maybe you should read Shakespeare.”

“Then most Americans won’t talk to me. If I quote a golden oldie by Spyro Gyra, I can get laid.”

I pushed him. “Could you get to the story?”

“All right, all right. Jesus Christ.” He tented his fingers. “Here’s the dope. When Americans fled Saigon in 1975, you’ve seen the footage, folks hanging off helicopters and scaling the walls of the embassy, the Trang family had no need for such whoop-it-up fireworks. Uncle Binh and his wife, Suong, worked for the Americans. He’d been an aide to General Westmoreland. A military man himself. Privileged and pampered, he was fed rice that smelled like lotus blossoms. Slept under mosquito netting. Used toilet paper flown in from California. So the U.S. had to get them out before the Commies put them in bamboo cages, sent them to reeducation camp, and smashed out their teeth. They got to an air force base a day or so before the craziness. Flown to Guam, put in huts, not makeshift tents like the rest.”

“Who exactly?” Hank asked.

“Well, Anh’s mother and father, who was Binh’s brother, two young sons, babies, a year or so old, maybe. Uncle Binh and his wife. She was a translator at the embassy. Suong, her name. A package deal.”

I sat back, nodded. “Safe in America.”

“That’s the problem,” Brandon went on eagerly. “They settled in Bristol, maybe because Uncle Binh, trained in Nam as an military engineer, was given a cushy job at New Departure, General Motors. I don’t know. According to my dad, they lost energy.”

“Meaning?” Hank asked.

“Think about it, man. It was like they had it all in Saigon, and they still wanted that world. But, hey, it’s America. Every step they took here reminded them of what they lost. Perfumed sheets and lotus tea. They still believe the Commies will crumble, all these years later, and they can go back. So they…they float in space. They wait. Hover over America like ghosts.”

I summed up. “America as a way station.”

“Exactly. They got no interest in America. It’s just the country that once promised them a safe Vietnam, then broke that promise. Promised them a good life, and then broke that promise.”

“But how did they end up in a housing project?” I asked.

He took a moment to answer. “As I said, no energy. And real bad luck. Fate. Buddha shopping at a different strip mall. Uncle Binh had some sort of accident at work, crippled, lost his job. His wife worked in a grocery store but got fired. So she and Uncle Binh live on disability in a dingy apartment down the street from the projects on Jefferson Drive.”

“That’s where Dustin’s folks live?”

“Mother,” he corrected. “Mother. His older brother, a jackass in his forties now, drifts in and out. A loser. Meth junkie, probably. Truck driver. Carpenter. A

sshole—pardon my French. Drug dealer, so they say. Prison time. The younger brother married a welfare Rican and got a hundred sniveling brats.”

“Father?”

“That’s the interesting part of the story,” Brandon confided. “You see, the whole bunch settled into poverty, food stamps and welfare and cash-under-the-table jobs on construction sites, but the lazy mommy gets pregnant when she’s in her forties. Like—late forties. A big surprise. No one is happy. And one night, a snowy night, urban legend tells me, they were driving to the hospital on Federal Hill and daddy swerved to avoid a falling branch on Route 6, crashing into a light pole. Dead at the wheel. Mommy goes into labor with the help of a passing cop, and little Anh Ky is born in a squad car off School Street.”

“Good God,” Hank said.

“That’s not the half of it. Ailing mommy is stuck with a squawking brat. She wants to watch Let’s Make a Deal all day long on her crappy TV, but there’s this little snot that took her husband’s life. Sort of. Little Anh Ky, crapping his pants and wailing, his mommy too tired to walk the five feet to change him.”

I shook my head. “Poor kid.”

“Yeah, sure. He turned into this—real embarrassment. Look at him.” Brandon sighed. “End of story. The winter apple.”

“What?”

“My dad said that’s what peasants in his village called such babies. The old sagging tree in the orchard surprises with a sudden apple. Out of season. In the winter of your life.” He waved his hand. “That’s Dustin. Gnarled, wormy, worthless. A winter apple. They never knew what to do with him. So they ignored him. He grew up by hiding away in the Bristol Public Library.” He grunted. “And the goddamned Lions Club pays for him to walk these expensive halls.”

Child of My Winter

Child of My Winter No Good to Cry

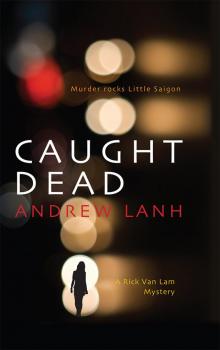

No Good to Cry Caught Dead

Caught Dead Return to Dust

Return to Dust