- Home

- Andrew Lanh

No Good to Cry Page 5

No Good to Cry Read online

Page 5

“And our little criminal? Simon?”

“The last of the brood, always battling his father’s whip. A bright bugger, I’m told, but a handful. The sixteen-year-old who rebelled against books and teachers and—his family. Suspensions, shoplifting, absenteeism, smart-mouthing the world. A teacher called him ‘Sy’ one day and someone morphed that into ‘Saigon Kid.’ Which he liked a lot. Rumor has it—courtesy of Big Nose—that he got a tattoo of that on his bicep.”

“At sixteen?” My voice crackled.

“God, how shockable you are, Rick. One of his buddies did it. There’s a shot of it on his Facebook page. On Instagram. I checked him out.”

“Does his father know? His mother?”

“Maybe we’ll find that out now.” Hank pointed up the street. “Let’s go. They probably think we’ve changed our minds.”

We pulled back in front of the small house and I switched off the motor. A curtain moved in that same upper dormer window and a small face glanced out, disappeared again.

“Don’t mention the tattoo, Rick.”

I smiled. “Makes him easy to identify in a police lineup, no?”

“We’re here to save him from a murder charge.” Hank’s eyes got wide.

“Let’s just start with a steaming bowl of chicken soup.” I tapped him on the forearm. “Let’s move. I think everyone in the house is watching us.”

Chapter Five

The front door swung open before we rang the buzzer. A small man dressed in a faded blue denim work shirt and dungarees rolled up over his calves stared at us, his face tight. A muscular man, sinewy. Quietly, he sized us up and then thrust out his hand, pumping my hand and then Hank’s. His palm was moist, but his grip was firm. Callused fingers, a bandage on his thumb.

“Mike Tran. Come in.”

He had a gruff voice, scratchy, and his free hand held a burning cigarette, the ash ready to fall.

But he didn’t step back, locked in that position, until a voice from behind him prompted, “Minh, you gonna stand there all day?” His eyes flickered as he turned to face the woman who approached from behind. She lovingly touched his elbow as he moved aside.

She introduced herself. “Soung Bach Pham. Call me Lucy. Everybody does.” She winked at her husband and grinned. “Minh ain’t used to company.”

He clicked his tongue but looked relieved. They exchanged glances—companionable, warm, necessary.

Lucy was as small as her husband, but slender, wispy almost, with a delicate oval face and a cupid’s-bow mouth that brightened her look. She blinked quickly, a nervous habit perhaps, but her eyes glistened. They looked—“happy” is the word that came to mind, but happy with wariness. We held eye contact for a second, but she broke the look.

“Chao mung ban!” She bowed. Welcome! “It’s Sunday morning,” she sang out. “We have mi ga.”

“Cam on.” I thanked her.

We were ushered into a small dining room that seemed even smaller with an oversized walnut table and chairs, a breakfront taking up one wall, and an illuminated cabinet filled with cardboard boxes—packages of rice noodles with brightly colored Chinese lettering, boxes of straws and napkins, a shelf of mismatched old dishes and glasses. The family storage bin. Chopsticks and bowls were already laid out on the table.

When I glanced through the doorway into the kitchen, I spotted a teenage boy bent over a textbook at the table. Was this Simon? If so, my stereotyped judgment was challenged because the boy looked classically studious—goggle glasses, scrawny shoulders, a picked-at complexion. For a moment he looked up, distracted, probably bothered by my gaze, but there was no expression on his face. His face dipped back to his book. A pencil gripped in his hand scribbled something on a notepad.

Lucy Pham saw me looking.

“Wilson, come say hello.”

The boy didn’t move until his father stood up. “Now.” A loud command. “Now.”

The skinny boy, pushing up the eyeglasses that kept slipping down his narrow nose, ambled into the doorway.

He grumbled, “Hi.” A half-wave. A cellphone beeped in a baggy pocket of his khakis, and he turned away. “Sorry. I got homework.” He pointed back to the kitchen. “I don’t wanna be late with my paper.” He looked back at his mother. “I told you—call me Will.”

“Eat first.” His father’s voice was firm.

“Mom told me to eat before.” He glanced at Hank and me as though the presence of strangers would inhibit basic digestion.

Lucy spoke up, apology in her tone. “Mike, he’s had his bowl already. I figured you want to talk…alone…”

That didn’t make Mike happy. “You could’ve told me.”

Lucy beamed. “Wilson is at Kingswood-Oxford. A scholar, my boy. A letter from Obama last year.”

Wilson had already returned to the kitchen table. He let out an unhappy grunt, a teenager recoiling from a parent’s praise to strangers.

Within seconds a young girl stepped into the doorway, but the look on her face suggested she’d been ordered to make an appearance.

“This is Hung. We call her Hazel.” Lucy draped her arm around her daughter’s shoulder. “Wilson’s twin sister.”

The young girl was beautiful, slender like her mother, with her mother’s delicate face. She didn’t look like Wilson, to be sure, but then his face was masked by the oversized black-rimmed eyeglasses. She wore a slight trace of pink lipstick, a hint of eye shadow, a bulky white cashmere sweater pulled down to reveal a bit of her left shoulder.

Yes, I thought, a younger version of her mother with brilliant black hair, lazy eyes a little too close together so that she looked as though she were always in deep thought—and a creamy complexion that looked painted on. A far cry from her dark-skinned father. But she had her father’s blunt chin and wide nose, though both seemed to enhance her Vietnamese features. A charming package.

I glanced at Hank who was blinking a little too wildly, his eyes riveted to the pretty girl. Awkwardly I kicked him under the table and startled, he yelled out.

“Ouch. Christ, Rick.”

“Sorry.”

But he knew what I was doing. A sly grin covered his face as he sent a half-wave at Hazel Tran.

Hazel mumbled something about not being hungry, studying to do, and fled upstairs. Lucy apologized for her. “The twins have just turned eighteen.” As though their newfound majority explained their behavior.

For a while the business of this visit was avoided as we ritualistically enjoyed the mi ga. Lucy rushed back and forth into the kitchen, carrying out trays of bean sprouts, thin yellow noodles, chopped cilantro and lettuce, spices. Hot steaming broth, delicate slivers of glistening white chicken breast floating in a tantalizing broth. My brow got sweaty as I leaned into the succulent soup, using the chopsticks to stir the aromatic liquid. Delicious, one of the best, which I noted. Lucy beamed. Hank ate his soup so rapidly, slurping noisily, that Lucy snatched his bowl and refilled it. I sipped aromatic jasmine tea, strong, sweet. I sat back, happy.

“An nao!” Lucy said over and over. Enjoy yourself.

Mike Tran cleared his throat. “I will talk of money now.”

I held up my hand. “Mr. Tran, not yet. Could we talk about your boy first?”

“Mike. Call me Mike.”

I nodded. He nodded. Lucy paused as she began lifting bowls from the table. In a low voice I barely understood, she said, “Simon.”

“Yes,” I said.

In the kitchen Wilson coughed. I looked at him. He’d stopped reading, staring at us with an icy look, but then he returned to his textbook.

Mike Tran cleared his throat again, confused. He looked at his wife who dropped back into her seat, interlocking her fingers, resting them on the table.

Mike Tran glanced toward the kitchen. “Wilson, take your books up to your room.”

The boy hesita

ted. “Pop.”

“Now. We have family business.” He pointed to the stairwell.

“I’m family.”

“Now.”

Reluctantly the boy cradled his textbook to his chest and climbed the stairs, but slowly, as though afraid he’d miss some conversation. No one spoke until he was out of sight. But from my chair at the end of the table, at angles to the hallway, I spotted the tips of his sneakers as he sat on the top stair, out of sight, listening.

Lucy, fluttering, pointed to a family photo on the sideboard. “We are a good family. Hard working.”

Mike grumbled. “You don’t need to say that, Lucy.”

“I like saying it.”

“Not now.” His look froze her.

She was shaking her head as she reached for the picture. “I’m sorry. A good-looking family, no?” Her fingertips grazed each member. Mother and father in Sunday-best clothes. Mike in a stuffy ill-fitting suit. Lucy in a simple dress, a gold necklace around her neck. A goofy-looking Wilson with a bizarre cowlick, annoyed, his mouth open. Hazel in a model’s pose, her head tilted at angles to the camera, lips parted. A third boy, older. “Michael,” she noted. “Our oldest. At Trinity. A National Merit Fellow. Brilliant.” Tall, striking, with a long, angular face, his head turned away from the camera.

Then her fingertip tapped the smallest boy tucked into the shoulder of his father. “Simon.” Her voice trembled at the word. “Our youngest.”

“Tell me about him.”

Mike waited a moment, collected his words. He wasn’t happy doing this. “The youngest lives in the shadows of the others. Never a student, didn’t like books. But a bright boy, my Simon. Quick, sharp, funny. He…we could laugh.” A trace of pride in his words, though he looked down into his lap. When he looked back up and into my face, he swallowed his words. “My shadow. Not like the others—me.”

I knew what he meant. Staring at the family photograph, the family illuminated by a photographer’s garish brush, the differences hit you. Young Simon, small and compact like his father, a bantam fighter, was dark-complected. Indeed, he could pass for a black kid. Or maybe Spanish. His father’s rough, honest gaze. Not so the others with their mother’s fairer skin, though they still carried their father’s features. Simon, the last born—and his father’s reflection.

Mike went on. “Always had trouble in school. Skipped classes. Fought back. Doesn’t go now—a dropout.”

My eyes drifted toward the living room. A wall of awards—plaques, school honors, embossed certificates, blue ribbons. A family’s wall of fame in eight-by-ten frames from Target. I breathed in. “I thought he’d be here today. I’d like to meet him.”

Mike looked at his wife, who turned away. “We told him you were coming—to help us, we told him—but he gets angry. And he runs off early this morning.” A helpless shrug. “He’s always been…a runner. You yell at him—he disappears. I lock him in his room, but he escapes.” His voice broke. “I made him a prisoner but…” His voice trailed off.

“But I need to hear him out,” I said.

A mumbled voice. “Some days we never see him.”

Hank spoke up. “He’s facing serious charges. A man died.”

Mike winced; his wife gasped.

The tapping of a nervous foot. At the top of the stairs a boy’s sneaker moved.

“I told him.” Mike’s hand balled up into a fist. “That detective came here, that Ardolino. Simon didn’t make it better. They took him and his buddy Frankie in for questioning, real quiet-like, me trailing behind all confused, but Simon yells and runs like a nut. Frankie tried to slug one. They throw them into a room to calm down.” His voice a shout. “My boy is doing his best to go to jail.”

“Tell me about his earlier arrests. Shoplifting. Muggings. Drugs. Four months in juvie.”

At first his voice was so soft I had trouble hearing him, but then, banging his fist on the table so that the plates shook, he roared, “A foolish, crazy boy. He always tells me he’s not good enough—smart enough—for the family. Christ Almighty. Even when he was small, he got in trouble. To everything—no, no, no. Fights me.” A glance at his wife. “I demanded my kids be good in school. I…I locked them in their rooms at night. No nonsense. Study. They were not gonna have my life.” A thin smile at Lucy. “I mean, my life is good, but I wanted…” He stopped. He nodded at her.

Lucy finished. “The best in America.”

“Simon fought me. He used to follow his older brother around, like hero worship, Michael this, Michael that. But then Michael goes to Trinity and says life in this house—the junk heap in the front yard—embarrasses him. Little Simon got no one to talk to. Bad grades, mouthing off to teachers.”

“Where did he meet this Frankie Croix?”

Mike’s face closed up. “A bad apple, that one. Sneaky, rotten. I know, I know—I excuse my boy and blame the other. I don’t excuse my boy. But this Frankie hangs out on Park Street in the Spanish neighborhood, drifts over to Little Saigon, maybe to buy drugs, finds this gang of boys…”

Lucy broke in. “The VietBoyz, they call themselves.”

“A gang?” I turned to Hank.

“Yeah, I heard of them. A local band of thugs—the underbelly of Little Saigon. Petty criminals, mostly. Not exactly BTK.”

I squinted. “What?”

“Born to Kill, Rick. Remember that notorious Vietnamese gang that made headlines with a wild shooting at a funeral in Jersey? Based out of Canal Street in Chinatown. They challenged the local Chinese tong gangs. The FBI moved in—closed them down. Murder without remorse—that bunch.”

“But years back, no?”

“Shadow gangs still pop up. Phantom gangs.”

“And Little Saigon in Hartford?”

“Yeah.”

Mike added, “Lost boys hanging together, stealing stuff from groceries, trafficking drugs, flipping off the cops, extorting money from old Chinese and Vietnamese store owners, payoffs from scared shopkeepers, that sort of thing. They just rob their own. Intimidate, frighten.”

“How many gang members?” I asked.

“Dunno.” Mike looked off as though thinking. “Mostly Vietnamese, some Chinese, some troubled white boys. Ex-cons. But my Simon found his way there. Lots of street boys do. You know, I followed him there one time. Some old industrial building, closed up. The thugs want young kids—do their bidding, follow orders.”

“Soldiers,” Hank went on. “Street soldiers.”

Mike was animated now. “Not in school but hanging in the front room of an abandoned store on Russell, off Park Street. VietBoyz. With a z. One word. You see the graffiti on the wall.”

“Simon’s a member?”

Mike didn’t like that. “No, no. He, well, stops in there. Him and Frankie.”

“Best buddies?”

He sighed. “I guess so. Simon and this Frankie got caught up in street stuff, the two of them like brothers, running the streets, dressing like punks. I forbid him to leave the house but he…runs off. He wanders back. I can’t control him no more. I guess they mugged this one old Chinese guy, asked for his cash but didn’t take it, pushed him around. Then, drunk with it, did more and more and more. Shoving, just pushing folks around, knocking into people. But the drugs. Shoplifting. Worse and worse. Stealing cigarettes from a gas station.”

“Then the police caught them in the act.” Lucy drew her lips into a thin line. “Thank God.” She whispered again, “Thank God.”

Mike let out an unfunny laugh. “Simon confesses. Blabs the whole thing. Like he’s proud. The judge sentenced them to four months at Long Lane. Simon tells us he hated it there. Rough boys, fights, cruelty, mocking by the authorities, everybody telling you you’re a piece of shit. Back home, he still runs the streets—it’s like it’s in his blood—can’t help himself.”

“But he still goes to…VietBoyz?”

“No more crime?”

A fatalistic shrug. “I don’t know.” Then, “Probably.”

“But he hated juvie.”

“Maybe he thinks he won’t get caught,” Hank added.

Mike grunted. “Kids think they can get away with murder these days.”

Immediately he regretted his words. “I don’t mean…no…he wouldn’t…”

“Did he talk to you about the latest attack? The death of Ralph Gervase?”

Mike’s eyes flashed. “You know, I asked him after we got back from the police station. Ardolino told me they were getting evidence against him and Frankie. Convinced, they said, he’s back to no good.”

“But Simon denied it?”

Again his fist slammed the table. “Yes.” He locked eyes with mine. “You know, that first time, dragging Simon to juvenile court, dealing with lawyers, hanging out in courtrooms, talking to the judge, my little Simon dressed in a suit too big for him, all those times I got him to talk. We never talk. But then he did. Maybe he was scared. I don’t know. He admitted everything. No reason, he said, the nonsense he did. Just for the hell of it. Something to impress the guys in VietBoyz, maybe. But after this last time we talked again. He—like sought me out. I’ll tell you, Rick Van Lam, he swore to me this ain’t his doing. ‘But nobody’ll believe me,’ he says to me. ‘I believe you,’ I said back. And he starts to shake. My boy, shaking. He ain’t never did that. A hard nut, that boy. This black sheep. ‘I ain’t done it.’ And I told him again, ‘I will call someone who will believe us.’” He pointed a finger at me. “You.”

Lucy tittered nervously. “Do you believe us?”

I said nothing.

“Simon don’t lie to me.”

“I want to talk to Simon,” I said.

Child of My Winter

Child of My Winter No Good to Cry

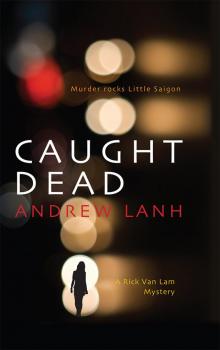

No Good to Cry Caught Dead

Caught Dead Return to Dust

Return to Dust